The UN has described the unfolding disaster in north-eastern Nigeria as the “greatest crisis on the continent” – the full extent of which has only been revealed as extremist militant group Boko Haram is pushed back.

The UN estimated in December that 75,000 children are at risk of dying of hunger in the region, as it deals with the aftermath of Boko Haram violence.

The agency also says that as many as 14 million people are in need of humanitarian aid in the region, the epicentre of the seven-year insurgency which has claimed more than 20,000 lives and displaced more than 2.5 million people in Nigeria and neighbouring countries (Niger, Cameroon and Chad): of the 14 million, more than half are considered “severely food insecure”.

In Nigeria, three states have been particularly badly hit: Borno, Adamawa and Yobe.

In the midst of this food crisis, at least one lone Catholic priest is trying to shed light on the situation of hundreds of local IDPs, left – with no assistance – to die of ’emaciation’ and ‘hunger’.

Father Maurice Kweirang, in charge of St. Theresa Catholic Church’s IDP camp in Yola, capital of Nigeria’s north-east Adamawa State, told World Watch Monitor his church is providing food to a thousand people in the camp.

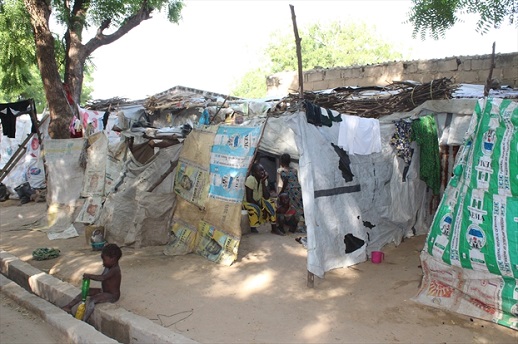

But hundreds of others are not receiving aid as the State denies their existence. It’s said the presence of IDPs is bad for business in the State capital.

”The Church is not able to feed them because we have limited capabilities and we cannot extend our support to all the IDPs outside the camp” laments Fr Kweirang. He said ”we provide food once a week to those living in host communities, and others living on their own. 3856 households are receiving our weekly food distribution, regardless of their religious background”

”I alerted some humanitarian organizations asking if they could assist. But they said they have moved away from ’emergency support’ to ‘livelihood’ in neighboring Borno State, because the Adamawa State’s latest report does not indicate any presence of IDPs in the latter.

The authorities in Adamawa have forced IDPs to leave camps without providing any support. Right now, there are only 7,000 IDPs in camps run by the government. But they’ve been asked to vacate the camps by next Wednesday (30 March). However the number of others living in host communities and villages around Yola is even higher.

And the presence of thousands of Nigerian refugees forcibly sent back home by the Cameroon government has worsened the food crisis in the region.

On Tuesday (21 March), the UN refugee agency criticised Cameroon’s decision to forcibly relocate its Nigerian refugees – despite an agreement aimed at ensuring the voluntary nature of returns.

While acknowledging the generosity of the government of Cameroon – and local communities who have been hosting over 85,000 Nigerian refugees – the UNHCR called on Cameroon to honour its obligations under international and regional refugee protection instruments, as well as Cameroonian law.

Cameroon rejected the UNHCR’s accusation and said people returned willingly. But according to Fr Kweirang, thousands of refugees have arrived in recent weeks.

”It’s difficult to give an exact figure of those ‘returnees’. I only saw the first batch: they are about 10,000. The second batch is yet to be confirmed but it will be higher than 10,000. There are still others – over 60,000 – trapped in northern Cameroon”.

He said they are all in very bad shape. A local TV station showed pictures of them shedding tears. They looked traumatized and are very skinny. They said the Cameroon security forces treated them badly, as if they were suspected Boko Haram members.

Though they are back in Nigeria, these refugees can’t go back to their communities for security reasons.

Most of them come from Gwoza and its surrounding areas where Boko Haram is still active. Militants still have camps around the Mandara Mountains, from where they continue to carry out attacks against villagers: stealing food, burning properties and kidnapping girls and women.

Kweirang said there’s a limited military presence: the army may carry out sporadic operations and then relocate to Madagali or Bama.

”Our team went out recently to assess the situation. They visited some IDPs who returned back to their communities, but only found that most of them are emaciated and looking unwell” said Fr. Kweirang. ”Both adults and children show acute signs of acute malnutrition. We brought some of them to our clinics for medical treatment, but we couldn’t keep them. They are living with relations in Yola and in surrounding communities”.

No-one is looking after them. Some are beggars, walking in the streets, or from door to door looking for food, while others are trying to get small jobs. But nobody is able to take them because most of the construction sites have stopped work, points out Fr Kweirang.

”The church has written to donors for support. But for now we haven’t yet received any response”.

The humanitarian crisis unfolding in the NE of Nigeria is also a direct result of mismanagement of aid destined for IDPs, as Oliver Dashe Doeme, Bishop of Maiduguri, capital of Borno State recently confirmed: “Most of the donations from the western world do not get directly to the targeted people. Whenever interventions come, they always insist it must go through the government agencies and through this, such interventions go directly into the pockets of some individuals. Most of our politicians are corrupt”.

At a conference held in Washington DC last week, former Congressman Frank Wolf called on President Trump to appoint an envoy on Nigeria and the Lake Chad region to deal with the crisis, which Wolf said presents a serious security threat.

At the same conference, Peter Pham, director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, said “Conflict in modern Nigeria cannot be understood apart from the historical reality of colonialism”.

At the same time, the changing religious dynamics of the nation also must be considered, he added. Outsiders who “buy into no-longer-relevant narratives” cannot confront the problems Nigeria faces today, Pham insisted.