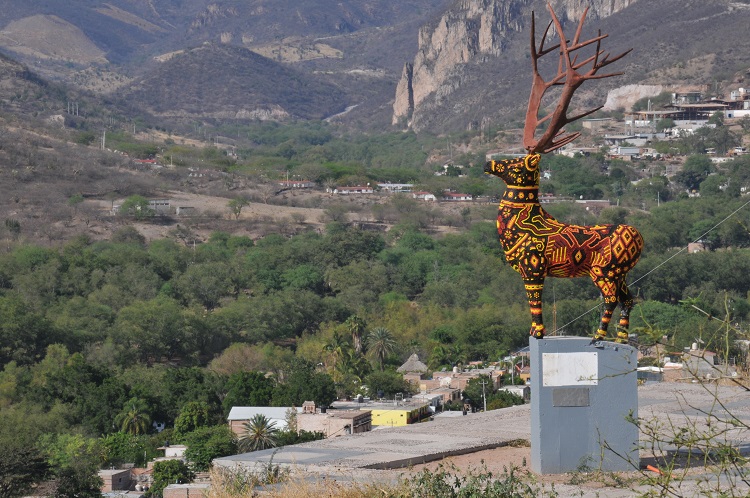

A giant statue of a deer stands high above the Mexican town of Bolaños, a symbol of its significance for the locals, who believe a deer-god protects them.

A giant statue of a deer stands high above the Mexican town of Bolaños, a symbol of its significance for the locals, who believe a deer-god protects them.

The belief dates back to when the Wixárika tribe first arrived in the area, in the western state of Jalisco, and encountered a deer which seemed to appear in front of them whichever way they turned. The tribe interpreted this as a sign of its promise of protection.

Today, in a community still dominated by members of the same tribe, the deer retains its significance as one of three local “gods”. The others are the maize upon which the community subsists and a hallucinogenic drug believed to invite an encounter with the spiritual realm.

For many of the tribe, to be Wixárika is to believe in the power of the three and to partake in the rituals and sacrifices offered to the gods – rituals involving blood, water and the use of the drug.

Yet not all Wixárikas believe in these practices. There are some, dotted around the communities of the surrounding mountains, who have become Christians and now don’t want to take part in the rituals.

Nor do they wish to give money to the tribal authorities – locally elected officials from among the native communities, which possess a certain degree of autonomy from the rest of Mexican society, and its laws.

In several communities, this has created friction. In one town, Tuxpan de Bolaños, which is two hours from the municipal hub, 30 of the Christians were forcibly ejected from the town.

A group of around 25 other Christians remains, but only because the Bolaños police force, which answers to the state government and not the tribal authorities, stepped in and refused to allow the others to be literally driven out of town.

The first group were initially dumped by the side of the road in sub-zero temperatures in January 2016. Eventually, the police came to their aid, taking them to the main town of Bolaños, but the Christians still carry the trauma of the manner of their displacement.

Then there is the trauma of being separated from loved ones – families were split down the middle, with children separated from their parents, and brothers from sisters – and forced to start again in a new town, miles from home.

The conditions in their new home remain less than ideal, with the 30 Christians inhabiting two storage shelters once home to crates of wine. Stepping inside, the lack of privacy is extremely striking, as is the suffocating heat. When all the Christians are together, sleeping in as many bunk beds as the shelter can handle, it must get even hotter. And goodness knows how husbands and wives find time to be alone together.

For the Christians still in Tuxpan, they are having to survive without their pastor – he was part of the evicted group – while their church building (erected in 2010 beside the pastor’s home) is now officially off-limits.

They now meet at the home of one of the women, Cenaida Bañuelos Sanchez, who acts as the group’s new spiritual leader.

Sanchez, who will be 50 in June, is one of those whose family has been split in two – her son, daughter-in-law and five-year-old granddaughter are in Bolaños. Another of her children, Yolanda, remains with her and her husband in Tuxpan.

A local indigenous missionary, Casimiro Martin Vazquez Mendoza – the man who brought the Christian message to Tuxpan – visits when he can. For 12 years, he has been travelling amongst his fellow Wixárikas, going back and forth between towns and villages which are hours apart. He has seen many accept the message he has brought, but he has also faced opposition.

The tribal authorities – particularly the shamans in charge of the religious rituals – don’t take kindly to his attempts to lead others on a different path, nor do they like it when the converts then refuse to contribute towards the sometimes-week-long festivals.

To some, the actions of missionaries like Mendoza might appear divisive – creating conflicts where there were none – but he is unapologetic.

“People need Christ in these ethnic communities,” he says. “There is a lot of need, spiritual need… It’s a very difficult, very sad [life]… There’s lots of poverty.”

Omar Rodriguez, who presides over a church in the state capital, Guadalajara, and also supports the Christians in Tuxpan and Bolaños, takes the same view.

“We are convicted that God gave us the Great Commission,” he says, “and when He said to go out to the whole world, that includes our indigenous friends and compatriots, who also have a need to fill the emptiness in their hearts.

“And what could be better for us to share with them than the real God, the King of Kings and the God of Gods. The God who created the [things] that these guys worship.”

The original pastor of the group, Jose de Jesus, who is now in Bolaños, adds: “Our Lord Jesus Christ changes us completely, He cleanses us completely, of all our filth, our greed, our hatred, and in addition to that He gives us His Spirit,” he says. “And therefore we are different, we no longer think about the [Wixárika] parties.”

It isn’t only religious groups offering help and advice. Eduardo Sosa from Jalisco’s Human Rights Commission says he hopes that in time Wixárikas who become Christians will be able to live harmoniously with their fellow people, though he says it won’t happen overnight.

“We need time, and that’s exactly what we don’t have,” he says. “The thing we need the most is the thing we have the least because the educational and sensitisation process is a long-term process.

“When Christians evangelise [in these communities], they experience the same difficulty as the Human Rights Commission does when it arrives with the ideology of respect for human rights in a cultural structure totally different from the rest of the Western world.”

Mr. Rodriguez, back in Guadalajara, shares his hope, saying: “We believe that our Christian community in Tuxpan can live in harmony with non-Christian Wixárikas because they have the same culture, the same principles. But some of their customs are not pleasing to God and our brothers have tried really hard not to practise those, which is part of the conflict that they have. However, we believe that living in harmony can be achieved, through intercession with the government and the state.”

To achieve this, Dennis Petri from Christian charity Open Doors, which supports Christians under pressure for their faith around the world, says the Mexican government has a balancing act on its hands.

“It’s very important that the right to the preservation of the indigenous and rural traditions are protected, and the Mexican Constitution provides for that … but that shouldn’t be used as an argument to violate the rights of individuals within those communities who decide to convert to another religion,” he says. “It’s essential that those rights are balanced.”

The Christians still living in Tuxpan are trying to build bridges. Newly elected tribal officials were recently invited to Cenaida’s home, where 180 “gorditas” (tortilla wraps filled with meat or cheese) were handed out to the officials, as a kind of substitute payment.

All the other locals had given money, but the Christians say they felt uncomfortable doing so, knowing it may go towards practices they disagree with. They say they hope their gesture will be received well and will help build relations with the new officials. A meeting has been arranged for 8 April, when the Christians will meet them to discuss what changes may be made to ensure a more harmonious existence.

Mr. Rodriguez says the meeting is a “very important” step and “could be the start of something”.

Signs of hope, then, that in time Christian Wixárikas may be able to live peacefully amongst their fellow people.