The Pope is making his first pontifical visit to Africa.

Jeffrey Bruno / Flickr / CC

After 48 hours in Central African Republic, I awoke to the first of the real days I had travelled 5,000 kilometres for. Everything until that point had been what any Lonely Planet traveller might discover and write in their blog: Ebola screening at the airport, a few bony, long-horned cattle in the streets, and sticky rainy-season humidity. Atmospheric, but not significant.

Today was different. A team of five of us was going to a rural church to meet with pastors and a few women leaders still living in the continuous trauma that was Central African Republic in July 2015.

I climbed out from under the mosquito netting and pondered how I had come to be in such a remote place. As Women to Women Coordinator for Open Doors International, a charity which works to support persecuted Christians, I had been following reports for more than two years about the armed conflict in CAR. I’d learned all about the terribly high price that Christian women and their families had been paying. In 2013, I had sat at my desk in France and wept for the Church in this land I’d only just realised existed. It had never before registered in my poor geographical understanding of Africa. Further, as a nominally Christian country with high Church activity, it hadn’t even been a blip on the Open Doors’ World Watch List of the 50 most difficult places to live as a Christian before 2014. Now it was #17.

So, as I washed from a bucket on a bare concrete floor, I prepared to soak up every nuance of the coming days as part of our Trauma Counsellor Training team. The program was designed to help the Church understand what had happened to itself as much as to offer paths to healing for broken relationships and lives.

Our lead trainer, Anne, warned us, “This group was particularly unresponsive to the material presented at the last training.” So I lowered my expectations. Would they express outright anger at the process? Or might there be stony silence? Regardless, we were there to offer what we could and if they showed up we could only trust that they saw value in the program.

We were returning to church leaders who were last visited when armed gangs of young militia still rode the streets of this small northern town. In 2015, the trauma was no longer being inflicted daily by the mainly Muslim Séléka killing and raping at will; thankfully, the only weapons I’d seen so far were carried by the UN vehicles sporadically patrolling the roads.

We arrived at a small building on a back street at 8:00 a.m. None of the roads that our pickup had bounced along were paved, just varying widths of red dirt, some kept smooth and others deeply cleft by the run-off of torrential rains. The mud daub on the outer walls of the one-room church looked fresh and spoke tentatively of hope and new beginnings. We stepped up over the threshold and into a worn room where a dozen well-dressed men and women sat on hand-hewn benches.

One of our team members, Céline, immediately walked behind the tall drums and began pounding out a compelling beat. The number of participants doubled and worship began. “Jésus m’aime, Jésus t’aime” we chanted and clapped hands with our neighbour. Singing through the French, Sango, and English verses gave us the time to look into the eyes of the person swaying next to us. Smiles were offered shyly and then more fully as we chanted how each individual in the room was deeply loved.

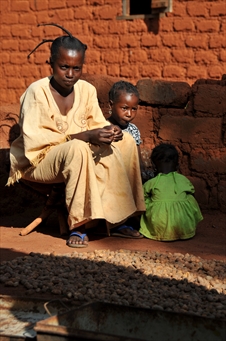

Tatiana Kado, 27, a mother of two, lost her husband during an attack by Seleka.

Courtesy Open Doors International

Then we sat and Anne stood. Calmly she greeted the group and offered an invitation to the participants to stand in turn and share what they had done with the material covered in the last session eight months ago. My heart skipped a beat; it was a bold move. Would they have anything to say?

A pastor at the front sprang up eagerly and greeted us solemnly. Enthusiasm rose in his face and his voice. He accompanied his story with grand gestures. “My brother in the Lord, Pastor Jérome, and I had it on our hearts to go to the groups occupying our town and speak to them of peace,” he shared. They organised believers to go with them and held an open-air service where the armed groups were encamped – groups of drugged and angry young men with machetes and machine guns. Two hundred of them showed up. There had been singing and powerful preaching. Even the women attended. Something special was happening.

In the days and weeks following this remarkable service, young men came, in ones and twos – fully armed – to quietly visit the pastors. Slowly but surely, the pastors’ attentive ears and words of empathy got past their anger. The armed groups began to climb into their pickups and drive away. “Ours was the first town to know peace!” the pastor told us proudly. Then he settled back onto a bench.

Another and another stood and told how he or she had had opportunities to walk with people along the path of reconciliation and healing. De-escalating tense situations in marriages and between fighting ethnicities in the north, organising training in the churches to pass on the message of grace and forgiveness, inviting rebel youths back to the churches, seeing HIV patients no longer carrying a stigma for their illness —the cycle of violence was being broken and individuals’ lives were being restored.

This was far beyond anyone’s expectations and sounded so Biblical, like Isaiah 2:4 come to life: “And they will hammer their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not lift up sword against nation, and never again will they learn war.” (NASB)

More encouragingly, many of the neighbouring ministers sitting before us had begun to work together to effect change in their communities. Through it all, I was struck by the consistency with which these local leaders went back again and again to visit hurting individuals in their midst, not allowing isolation to reinforce the trauma.

With a sense of wonder at all that God had been doing, the only reasonable response seemed to be to pause and praise the Lord. We began to pray, thanking Him that those present had practiced working together, reaching out to the hurting, and working quietly but effectively to spare their towns and villages further violence. My heart was overflowing. “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall see God.”

Over the next three days of training alongside the participants, I learned in even greater detail about how relational cycles of violence play themselves out in Central African Republic, both inside and outside the church communities. Anne presented models of healthy and dysfunctional relationships. We broke into discussion groups, and first with a small group of men and then with the few women, I delved deeper with them into the implications for their churches and ministries. Simultaneously, in the back of my mind, the Lord was using these models to enlighten troubled relationships in my own life.

Anne also gave us the example of the Biblical King David to consider. He grew from a largely ignored youngest son, surviving a troubled relationship with King Saul, to become the head of God’s people, both a lasting revelation of God’s heart and, uncomfortably, a disaster in many of his family relationships.

Martine Verpio, 55, the widow of Pascal Mendefra, who was killed by Seleka.

Courtesy Open Doors International

This is where the training got tricky for everyone. We shifted around on wobbly benches and unwieldy wooden chairs to avoid the sudden rainfall dripping through holes in the rusted roof. Then we focused our hearts on our assignment: to make parallels between David’s relationships and those in our own lives and those around us. For my part, as a foreign facilitator, I had a particular challenge: could I be that humble soul whom they could trust enough so that scary truths could be named without destroying anyone’s self-worth?

It is so hard for all of us to believe that there is no shame in acknowledging the specifics of our own cultural conditioning; it doesn’t matter where we’re from. Materialism is one of the deadly plagues where I come from; it alternately dulls the Church into complacency or tempts us into worry and frenetic behaviour. The Church in the Central African Republic was facing a very different cultural heartache: the shattering of families following violent attacks on women and girls.

This is what had brought tears to my eyes when I was still far away, and though I had come hoping to meet dozens of women being trained to counsel other women as they dealt with deep trauma, the reality is that it takes more effort to give women access to training than men. So Open Doors will be making those special efforts in 2016 to train more women in how to offer other women safe places in which to face their pain.

At least as important, though, were the honest conversations with the men about their key role in reflecting God’s compassionate character, both inside and outside the Church. A Church in a culture that highly values notions of honour and purity, even upside-down notions, is still a Church that should be primed to respond to God’s counter-cultural example of servanthood and purity of the soul. Holistic ministry is so beautiful — strengthening every part of the Church body to make its unique life-giving contribution so that the whole flourishes.

Pastor Jérome closed the three days with some insight into the perspective of the participants. “After the previous training,” he said, “we thought we would never see you [trainers] again.” (The visitors then had been under constant threat as they slept each night with the resonating sounds of gunfire, and refugee families crowded into their compound. The pickup truck we rode in still bore the mark of a bullet from the perilous journey the team made back to the capital.) “But, voilà, you came back.”

Relationships had been rekindled and strengthened. The church leaders were motivated afresh. Both men and women had a renewed vision for how healing could be brought deeper into families and of where cycles of violence could permanently be broken so that they could say for their children “… never will they learn war again.”

It would be a long road to full restoration, but with the peace that comes from knowing that God is at work, we said a warm “Until next time” to each other. Then, the five of us climbed into the pickup once more and drove away slowly past children playing in the after-storm glow on vibrant ochre soil.

To some, CAR remains a distant country on a map, a headline in the news. To me it’s a land of brokenness, yet full of hope.